Table of Contents

The landmark Roe vs Wade ruling once protected the constitutional right to abortion in the United States. Its reversal in 2022 didn’t just shake the foundations of American law — it sent ripple effects across the globe. From protests in Paris to new bills in India, the fall of Roe forced the world to confront a difficult question: what happens when something that was once a right is no longer?

This isn’t just a story about abortion. It’s about who gets to decide what you can and cannot do with your body. It’s about politics, religion, race, and power. And it’s about how laws made in courtrooms affect people in hospitals, homes, and everyday lives.

When we reflect on the predicament of a premature baby and the caregiver’s responsibility, we are confronted with a profound question: which holds greater importance?

Jane’s Spark: The Name That Started A Movement

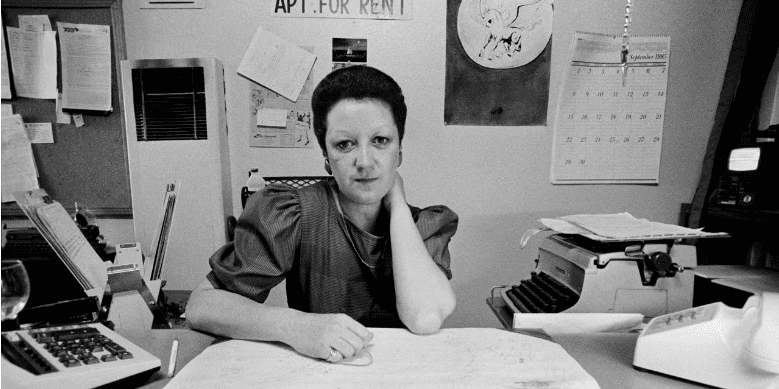

Norma McCorvey was 22, unemployed, and pregnant for the third time. She had struggled with addiction, was not in a stable relationship, and had already given her first two children up — one to her mother, and the other for adoption. When she discovered she was pregnant again in 1969, she didn’t want to carry to term. But Texas law made it virtually impossible.

That same year, two lawyers — Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee — were actively searching for a plaintiff to challenge the state’s abortion ban. They needed a real person, a current pregnancy, and someone willing to be the face of a legal battle. Norma’s situation fit their criteria.

Later, McCorvey recounted that when she asked why she was chosen, she was told:

“You’re white, you’re young, you’re pregnant, and you want an abortion.”

She agreed. Some reports claim she was paid a significant sum to participate, though this remains disputed and complicated by conflicting accounts. What is certain is that McCorvey never testified in court. She never had the abortion. And she didn’t fully understand the scope of the case until years later.

By the time Roe vs Wade was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas in 1970, she had already given birth. Her daughter — who would later be known as “Baby Roe” — was placed for adoption.

Despite being at the centre of the most consequential reproductive rights case in American history, Norma McCorvey remained largely on the sidelines. Her story was used, politicised, and retold countless times — but rarely in her own words.

And when the Supreme Court ruled in her favour in 1973, it didn’t change her life directly. But it changed the lives of millions of others.

Before Roe, Abortion Was A Shadow Operation

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, abortion wasn’t a right. It was a risk. If you needed one, you had three options: find a doctor willing to lie for you, travel out of state or out of the country, or do it yourself.

“Therapeutic” abortions were technically legal in some states — but only if a doctor declared the pregnancy a threat to the mother’s life. The workaround? Many doctors sympathetic to their patients would diagnose women as “mentally unstable” or “suicidal”, just to protect them. It was a quiet act of rebellion, often done behind closed doors.

For most women, though, abortion was an underground operation. Some used Lysol. Others inserted knitting needles. Clergy counselling networks popped up to help women navigate back-alley clinics or fly to places like Mexico. Activists like Pat Maginnis and the Jane Collective in Chicago even taught women how to perform their own abortions — not because they wanted to, but because the system gave them no other option.

When The Case Went Public, So Did The Country

By the time Roe vs Wade hit the Supreme Court, it wasn’t just a court case. It was a cultural earthquake.

From Texas town halls to college dorms, kitchen tables to clinic lobbies, Americans across every age, faith, and class were suddenly pulled into the conversation. Summer 1972 felt volatile. Charged. Even hopeful. Local newspapers ran heated op-eds, neighbourhoods erupted into arguments, and protests took over city streets. In a Gallup poll that year, 68% of Republicans said they believed abortion should be a private matter between a woman and her doctor. Yes—Republicans.

But belief wasn’t enough to stop the backlash.

Doctors who provided abortions were labelled criminals, even when they operated safely. Some had their clinics raided. Others were attacked. A few were killed. Dr George Tiller, a physician in Kansas, was shot in 1993. He survived.

The resistance was swift, strategic, and often violent. The Catholic Church condemned abortion as a moral violation, tying it to the broader Judeo-Christian heritage. Clinics were bombed. Protesters carried crucifixes and graphic posters. And politicians, realising they could leverage this for votes, shifted the debate from public health to public identity.

You weren’t just being asked what you thought about abortion. You were being asked which side you were on.

Meanwhile, underground networks had already been saving lives. Since the 1960s, women who couldn’t access legal abortion were turning to secret clinics, sympathetic clergy, and feminist groups like the Jane Collective. Doctors, nurses, and volunteers put their lives and licences at risk to offer safe procedures. Others—like Dr Jane Hodgson—went to jail for refusing to let women die in silence.

Still, the violence escalated. In Boston, two women were murdered. In Pensacola, Dr David Gunn was shot dead. Clinics across Tulsa, Atlanta, and Florida were bombed one after the other. The idea that Roe had “sparked” the culture war is misleading. The war was already raging.

Because this was never just about law.

It was about power. About whose pain gets believed. About whose morality gets enforced. About whose body counts as “worthy” of choice.

Even before the ruling, the consequences were playing out in real time. Women were crossing state lines. Teenagers were forced into motherhood. Survivors of rape were denied care. Others died after attempting it themselves—alone, scared, and bleeding.

So when Roe vs Wade was finally decided in 1973, it didn’t end the debate.

It lit a fuse.

In the late 1990s, the violence hadn’t stopped — it had escalated. The FBI released an audio tape of a caller who took credit for bombing two abortion clinics in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. His message was clear: “Next time, I’ll blow it clean off the map.” It wasn’t a metaphor. These weren’t just threats — they were promises of war.

Doctors were killed. Nurses were assaulted. Volunteers were stalked. The violence was deliberate, coordinated, and often framed as divine justice. And at the centre of it all were everyday people—clinic workers, security guards, women seeking abortions—living under constant threat.

Dr George Tiller, a physician from Wichita who had already survived one assassination attempt in 1993, was gunned down in 2009. Not in a clinic. In church.

And yet, amid the fear and fury, something else was happening too. Ordinary people from both sides—young, old, parents, students, pastors, activists—flooded the streets outside the Supreme Court. They weren’t just protesting. They were waiting. Holding their breath for a decision that could redefine American life.

On January 22, 1973, the ruling came. The Court had studied the Texas statutes. Reviewed precedents. Balanced state interests. And finally, declared:

“This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, or… in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether to terminate her pregnancy.”

That sentence—delivered by a mostly male court, led by a first-time Supreme Court advocate who had once had her own abortion in Mexico—changed everything.

It meant women didn’t need their husband’s permission. Or their father’s. Or their priest’s. Or their senator’s. They didn’t even need a reason, at least not in the early stages of pregnancy. The Court had recognised abortion as a constitutional right under privacy.

At least, that’s how it looked on paper.

Because while Roe did legalise abortion, it didn’t end the war. It shifted the battlefield. From underground clinics to courtrooms, legislatures, newsrooms, and living rooms. What was once whispered became law. And what became law became lightning.

So yes—Roe vs. Wade settled something. But not everything.

The Political Chessboard

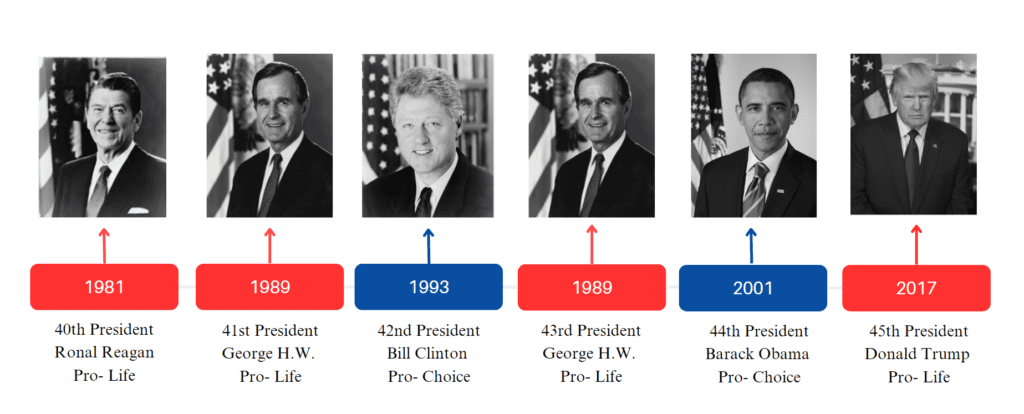

If Roe vs Wade was the courtroom battle, the real war was fought in the ballot boxes, pulpits, and policy backrooms. Abortion didn’t just become a political issue — it was weaponised into one.

The turning point was the 1980 US presidential election. This is when abortion stopped being a moral question debated in courts or homes — and became a vote-winning machine. The Republican Party, guided by evangelical leaders like Jerry Falwell and strategists like Paul Weyrich, realised abortion could unify and mobilise their base. Not because they cared deeply about foetuses — but because their original fuel, racial segregation, no longer had mass appeal.

Weyrich admitted it himself: the religious right wasn’t born out of Roe. It emerged when the IRS threatened to strip segregation academies like Bob Jones University of their tax-exempt status. But “religious freedom” was too abstract to stir a movement. Abortion, on the other hand, was visceral. It had imagery, rhetoric, and the illusion of moral high ground.

This wasn’t just ideology — it was choreography. Governors passed anti-abortion bills. Presidents stacked courts. State legislatures introduced trigger laws. And quietly, relentlessly, the judicial balance tipped. Norma McCorvey — Jane Roe herself — later said she felt like a pawn. Because she was.

The anti-abortion movement’s power wasn’t just legal or spiritual — it was political. In the hands of the right, abortion became a golden ticket to the White House. A litmus test. A purity check. A means to consolidate white evangelical voting blocs under one crusade: “life.”

But “life,” was selectively defined. Same lawmakers who banned abortion cut welfare. Shrunk healthcare budgets. Dodged questions on maternal mortality and childcare subsidies. Senator Nathan Dahm of Oklahoma, for instance, was filmed fumbling when asked why the state hadn’t secured basic parental support before outlawing abortion .

What we’re seeing here isn’t a moral debate — it’s a political chess game. One where women’s bodies are moved around for votes, their stories erased from the record unless they serve a narrative.

Meanwhile, the opposition — Democrats, moderates, even some pro-choice conservatives — stayed scattered. Reactive. Always defending, rarely strategising.

That long game worked. Not overnight. But over decades — from Bob Jones to Dobbs. From protest votes to Supreme Court seats. Roe didn’t just fall. It was pushed, prodded, and plotted into collapse.

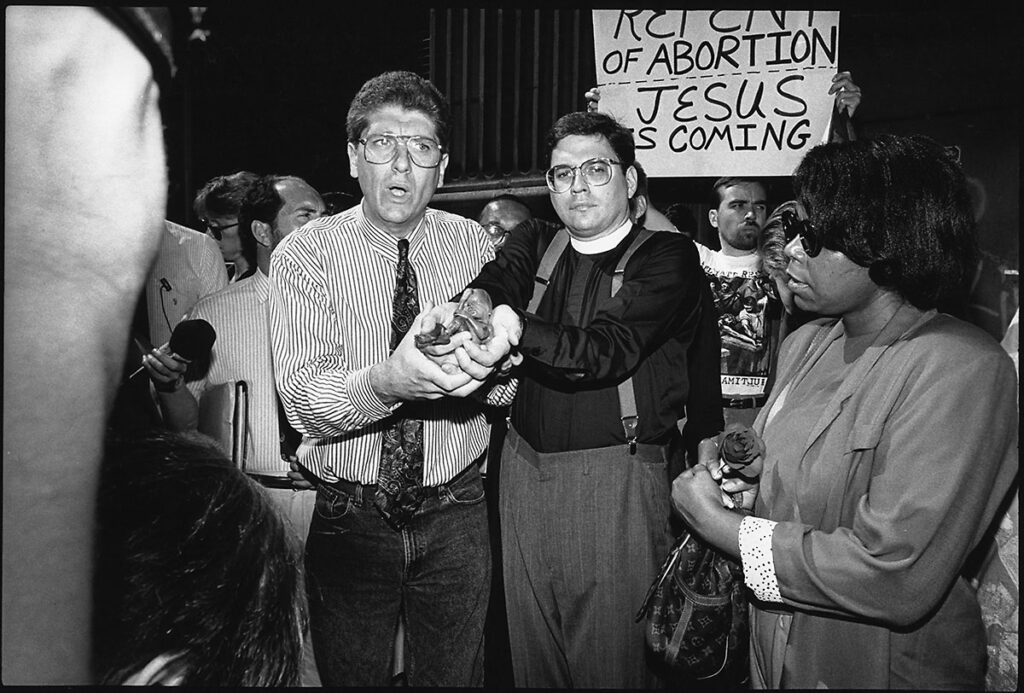

Operation Rescue

By the mid-1980s, the anti-abortion movement was no longer just campaigning — it was declaring war. And Randall Terry wanted to be its field general.

In 1986, Terry founded Operation Rescue with a chillingly simple slogan: “If you believe abortion is murder, act like it’s murder.” His group wasn’t interested in courtrooms or campaigns. They wanted chaos. The plan? Blockade clinics. Chain themselves to doors. Disrupt access, provoke arrests, and force the nation to watch.

Terry openly modelled these tactics on civil rights-era sit-ins. But while Martin Luther King Jr. used non-violent resistance to fight segregation, Operation Rescue twisted that playbook to restrict women’s bodily autonomy. Their protests began in Cherry Hill, New Jersey and spread to boroughs across New York — turning clinics into war zones of ideology and obstruction.

The rhetoric wasn’t subtle. Speaking to The Independent, Terry compared his movement to the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe: “We will make it to Berlin, and we will make it a crime to kill innocent babies from conception ’til birth in all 50 states. Every abortionist here in America should be tried for the killing of innocent babies.”

This wasn’t fringe energy. It had the backing of the Church. Cardinal John O’Connor of New York not only endorsed the movement — he urged nuns to abandon their daily work and direct all their efforts toward ending abortion.

Operation Rescue wasn’t just a protest group. It was a siege operation — fuelled by theology, media spectacle, and a strategy designed to push the country toward criminalising abortion by any means necessary.

The Nail In The Coffin

Operation Rescue didn’t just disrupt access to abortion — it disrupted American politics. The group, with its theatrical blockades and martyr-style arrests, managed to stir national sentiment, reframing abortion not as a private medical decision, but a moral emergency. In doing so, they converted thousands, helping build the public pressure that nudged Ronald Reagan into switching sides.

Though once a supporter of liberal abortion laws as governor of California, Reagan adopted a pro-life stance in time for his presidential run — not out of conviction, but calculation. The anti-abortion bloc had grown too powerful to ignore, and the Republican party began its slow but deliberate shift into a conservative stronghold on reproductive rights.

Decades later, this ideological push would find its most explicit flashpoint in Texas.

In 2013, Senate Bill 5 was introduced — a sweeping piece of legislation that proposed banning abortions after 20 weeks, requiring clinics to meet the standards of ambulatory surgical centres, and mandating that abortion doctors have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals. On paper, it was about safety. In practice, it was about control.

The bill would have effectively shuttered most abortion clinics in Texas. Protests broke out across the state — some in defence of the bill, many in outrage.

Enter Wendy Davis.

On 25 June 2013, wearing pink sneakers and a back brace, Davis stood for 13 straight hours on the Texas Senate floor. No leaning. No food. No bathroom breaks. Her goal: block the vote on SB5. Her words echoed with clarity and fire:

“No woman should be judged by someone else… These decisions are never easy, nor made casually or quickly. And those of you in the Senate should not make them casually or quickly either.”

She became a national symbol overnight. But her filibuster only bought time. The bill passed soon after in a second session — and the groundwork was laid for more aggressive state-level attacks on Roe.

Fast forward to 2022.

Donald Trump, having already stacked the judiciary with conservative loyalists — including Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett — delivered on the unspoken promise to the Religious Right. The court now had the numbers.

On 24 June 2022, in a 6–3 decision, the Supreme Court overturned Roe vs Wade.

The ruling did not simply revise abortion law — it deleted it from the Constitution. After nearly 50 years, the federal right to terminate a pregnancy was gone. Roe was no longer the floor — it became a ceiling shattered and swept away, leaving every state to legislate as it pleased.

The fallout was immediate.

Thirteen states had “trigger laws” that banned abortion the moment Roe fell. Thirteen more rushed in with copycat bills. In some places, even cases of rape, incest, or fatal fetal anomalies were not enough to permit an abortion. In others, pregnant women were turned away mid-treatment, forced to cross state lines for basic care.

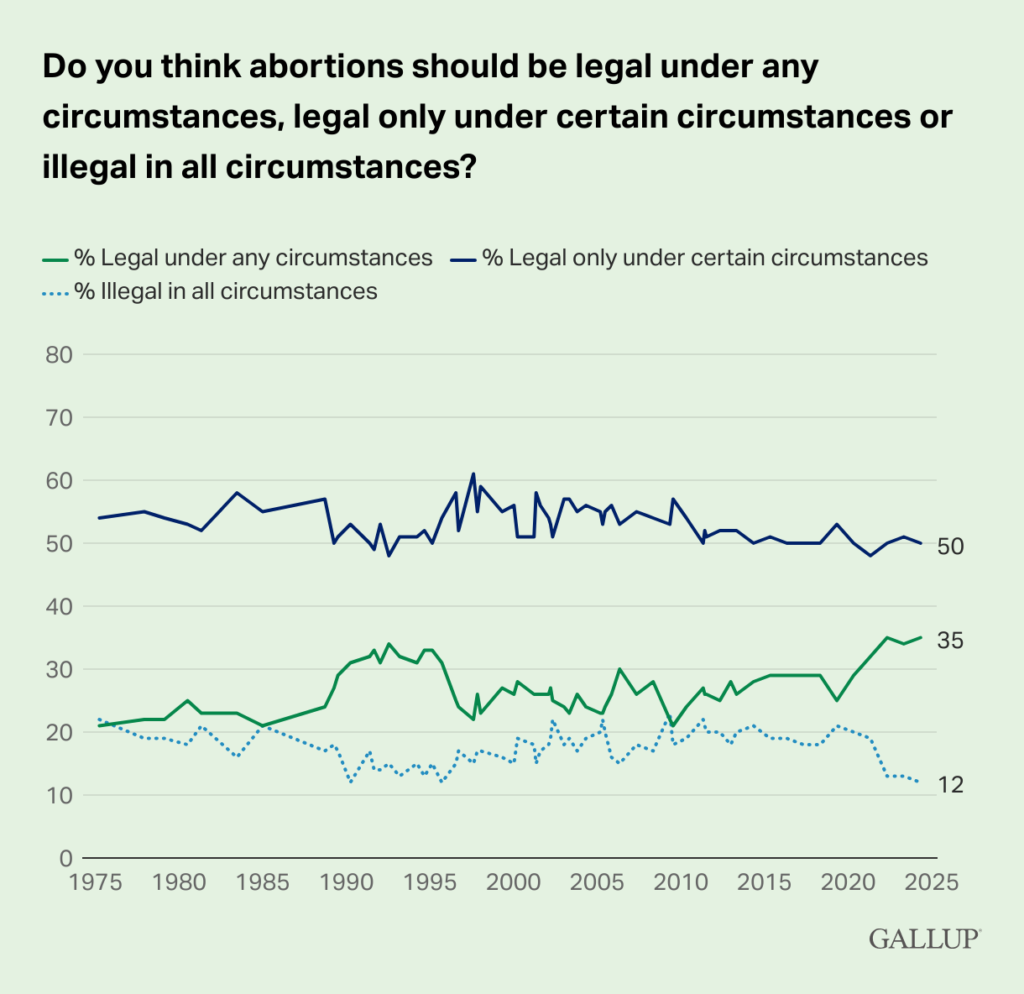

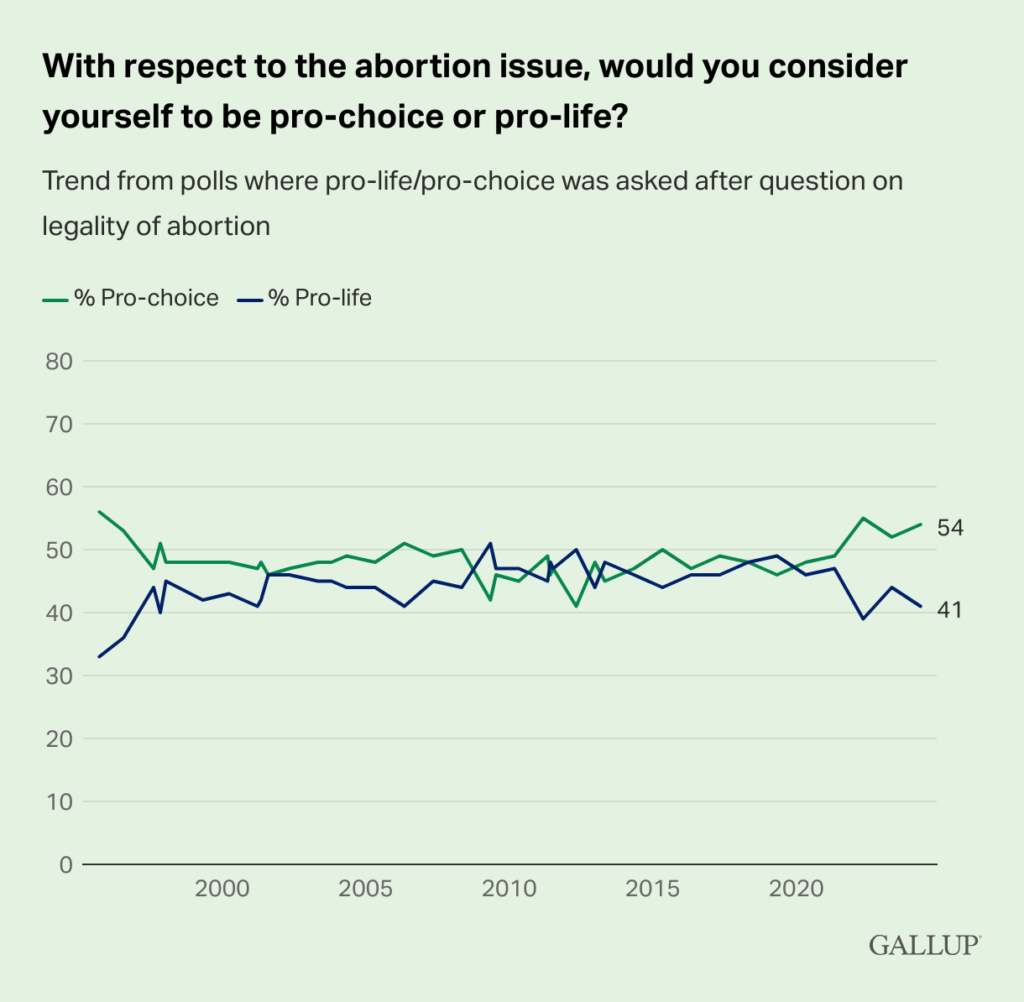

And yet, the data tells a different story.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, one in four women in the US will have an abortion in their lifetime — a figure that transcends race, religion, income, and ideology. These decisions are rarely simple. They’re driven by economic uncertainty, health risks, abusive relationships, parenting responsibilities, and personal readiness.

But in a post-Roe America, the law no longer cares why.

Access to reproductive care now depends on geography. In 21 states, abortion is either banned or severely restricted — and for millions, that means rights are conditional, choice is compromised, and control over one’s body is no longer guaranteed by the Constitution.

The Global Dynamic Shift

For decades, the United States wasn’t just a superpower in economics and defence — it was a blueprint. A country whose constitutional rights influenced parliaments and protestors alike. Roe vs Wade didn’t just change lives in the US. It gave momentum to abortion rights movements across continents.

Look at the 1970s:

Singapore passed its abortion act in 1970.

India followed with the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act in 1971.

France passed the Veil Act in 1975.

Italy legalised abortion in 1978.

The ripple was unmistakable.

The U.S. had long wielded soft power — not just through diplomacy or defence deals, but through its jurisprudence. Roe’s legacy, even beyond its borders, became symbolic of a country willing to codify reproductive autonomy. Until it didn’t.

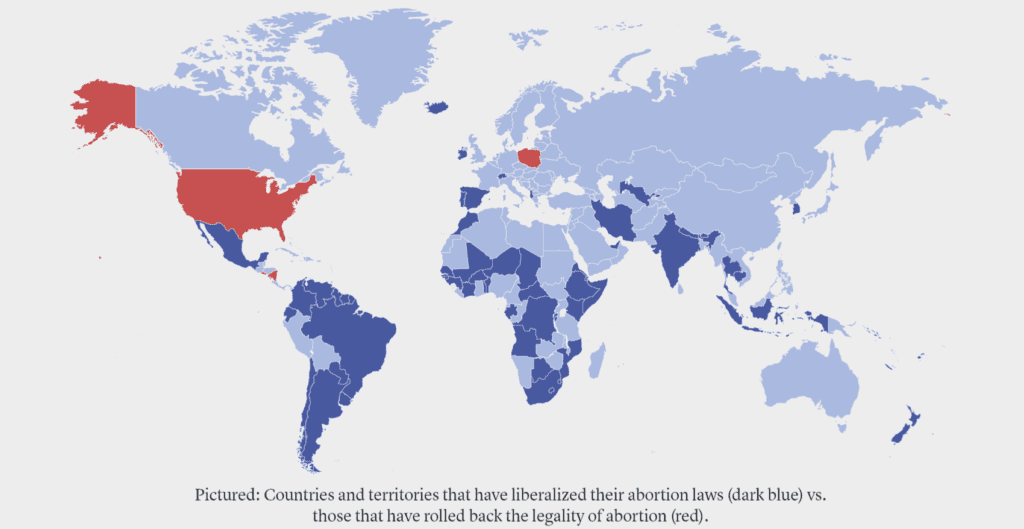

In 2022, Dobbs vs Jackson Women’s Health Organization reversed that arc.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion — effectively overturning Roe vs Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood vs Casey (1992). With one decision, 50 years of constitutional precedent collapsed. Power was handed back to individual states, and America became a global outlier — not for its liberalism, but for its regression.

The irony was stark.

While dozens of nations were moving forward — Chile, Ireland, Colombia, Argentina, Zambia — the U.S. began to walk backwards. Even countries where religion once dictated policy began separating belief from law. In contrast, America folded to a theocratic lobby disguised as constitutionalism.

But Dobbs didn’t just isolate the U.S. politically. It ignited a global fire.

The right of women to choose abortion will become irreversible.

President Emmanuel Macron

We’re sending a message to all women: Your body belongs to you, and no one can decide for you.

Prime Minister Gabriel Attal

The European Parliament condemned the Dobbs ruling as a direct violation of human rights, passing a resolution that called any regression on abortion policy an attack on dignity and democracy.

The message was clear: The U.S. was no longer the leader on this front. It was the cautionary tale.

Over the past 30 years, more than 60 countries have expanded abortion access. In many of these cases, the struggle wasn’t just medical — it was cultural. They had to fight religious dogma, gender taboos, and political resistance. But the direction of change was consistent: forward. Roe’s repeal shook that trajectory. It validated conservative movements across borders. It also, paradoxically, galvanised resistance.

Some countries used Dobbs as fuel to go further. Others feared the precedent — that progress isn’t permanent.

Because here’s the truth:

Abortion is not just about healthcare.

It’s about power.

And as the United Nations wrote in 2021, if we want a world with affordable, transparent, ethical abortion care, then abortion “must be taken out of the realm of politics.”

And yet — that’s exactly where it ended up.

The Ultimate Question

Abortion has never been just about medicine.

To some, it’s a private health decision — no different from a liposuction or colonoscopy. A procedure that belongs between a patient and their doctor, with no third-party opinion needed. That perspective calls for unrestricted access, free of stigma or surveillance.

But to evangelical conservatives, abortion is the taking of an innocent life. Groups like Operation Rescue, the 700 Club, and Family Watch treat it not as healthcare — but as homicide. Their goal is not just to restrict access, but to shut clinics down altogether, reframe abortion as moral corruption, and cast abortion providers as criminals.

This conflict has played out through the courts for over 50 years — from Roe vs Wade to Dobbs vs Jackson. Along the way, landmark cases like Whole Woman’s Health vs Hellerstedt and Family Watch vs Planned Parenthood have tried — and failed — to find neutral ground.

Is abortion fundamentally a religious issue? A political flashpoint? An economic question? Or is it, simply, a medical choice being politicised into oblivion?

Even the politicians couldn’t decide.

Ronald Reagan once signed one of the most liberal abortion bills in American history as governor of California. By 1980, he was rebranded as a pro-life crusader. George H.W. Bush was pro-choice before he wasn’t. Trump didn’t have to believe anything — he just had to play along. Abortion wasn’t about conviction. It was about votes.

And what about Norma McCorvey — the original “Jane Roe”? At the end of her life, she denounced the movement that had used her name. After years of public appearances for the pro-choice cause, she converted to evangelical Christianity and said she regretted it all. Her final act was to switch sides — yet both claimed her legacy.

The 1992 Democratic National Convention laid the optics bare.

Pro-choice activists brought images of coat-hanger abortions, women who died from illegal procedures, and signs demanding autonomy. Pro-life groups countered with blown-up photos of aborted foetuses. It wasn’t a debate. It was a media war — each side battling for the nation’s empathy through shock, grief, and guilt .

That war hasn’t ended. It’s only evolved.

The Sonogram Bill. The Partial-Birth Abortion Act. Mandatory waiting periods. Laws requiring sonograms and in-person counselling. Every restriction, every clause, adds another layer of psychological weight — without necessarily improving medical outcomes. In many states today, legal access exists in name only.

And now, with Roe gone, a woman in a red state may have no choice at all.

No matter her trauma.

No matter her poverty.

No matter her diagnosis.

She will carry the pregnancy.

Because her state decided it for her.

In the end, that’s the core conflict. A foetus cannot speak, cannot vote, cannot consent. A woman can — and yet, must fight to have her rights recognised at all. It’s not just about law or science. It’s about control.

Who decides?

Whose body counts?

Whose rights survive the courtroom?

The question isn’t ultimate because we don’t have answers. It’s ultimate because we keep asking — and still don’t agree who gets to answer it.