Table of Contents

Forget silent. In India, dementia roars for millions. Here, one in six cases resides, leaving families on the front lines of a brutal battle. Imagine: the vibrant woman who raised you forgets who you are. The strong father you leaned on needs constant help. This is the harsh reality for countless Indian families facing dementia.

Traditionally, care happens at home – a beautiful expression of love, but also a heavy burden. Limited access to trained help and a societal hush around mental illness leave families struggling emotionally, physically, and financially. This isn’t just about illness; it’s a fight for understanding and support.

We need to break the silence. We need more trained specialists. We need a safety net for families.

Through personal stories, this article dives into the heart of dementia’s grip on India. It’s a call to arms, a reminder that we’re all in this together, battling a foe that demands to be seen and understood.

This is a Long Read, But Not a Lonely One

Naveen Mahadevan, our co-founder, interviewed families caring for loved ones with dementia. Naveen, a photojournalist turned writer, brings his magic touch to the pictures and stories below.

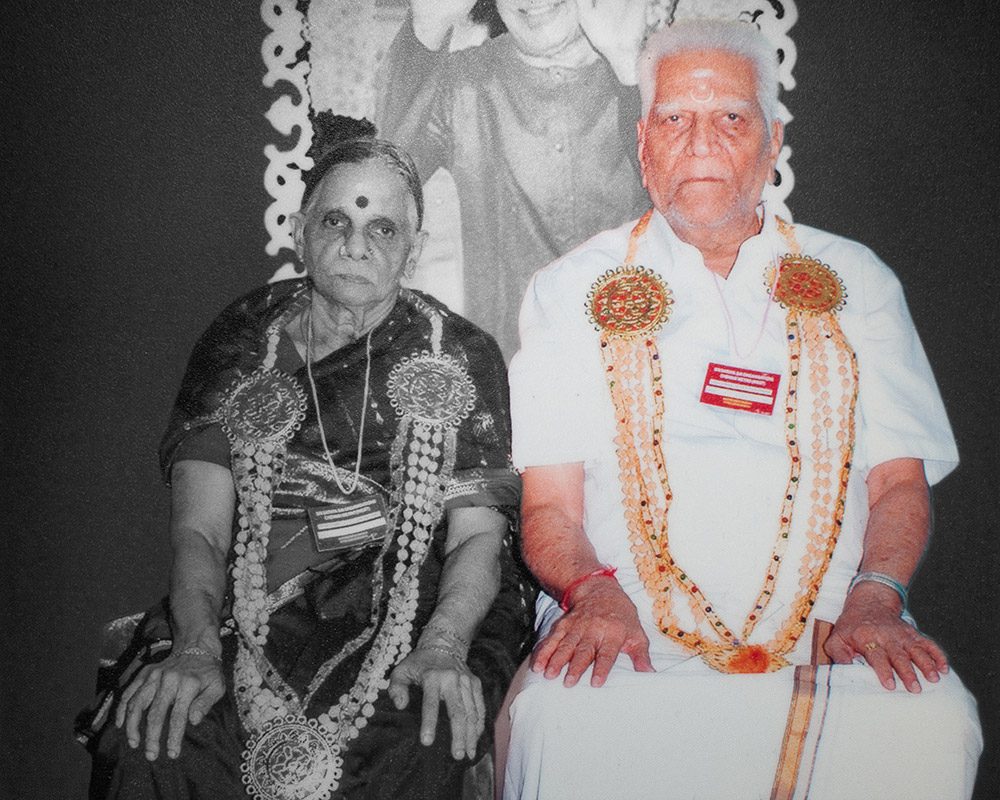

EN Nagaratinam’s Story

Tears well up in EN Natarajan’s eyes as he takes a moment to ponder over some of the things he cherished about his 101-year-old father. “Everything,” he whispers, wistfully. His father, EN Nagaratinam, recently succumbed to dementia, arguably the least understood of all serious illnesses, after a battle that lasted almost a decade.

Nagaratinam led a healthy lifestyle which included early morning brisk walks and clean eating habits. But all of this took a tumble once dementia took hold of his mind and body in his early nineties. He became completely dependent on his family for all his needs, a year or so before his passing. He first exhibited symptoms of memory loss in 2008, when he began having trouble recalling people’s names at his granddaughter’s wedding.

As dementia progressed, he lost his ability to comprehend written words and it was not long before his writing became illegible. A devout Hindu, he would spend a good chunk of time every morning offering prayers to God. “He’ll sit with the shloka book [during his morning chants] and when you check up on him an hour later, he’d be on the same page or holding the book upside down like a child,” said his daughter-in-law. His family could not connect the dots. Later, when other symptoms became more apparent, they turned vigilant.

We started noticing repetitive behaviour. He’d have left the dining table after his meal but after glimpsing us having our food, especially if there were sweets in the vicinity, he’d pull up a chair beside us forgetting the fact that he’d just eaten.

EN Natarajan (Father)

He was a no-nonsense family man who had earned himself a reputation as a diligent and scrupulous worker.

Daughter-in-law

At the core, he was a simple, austere man and impressed a great deal of discipline upon all his children.

Seethalakshmi’s Story

On the eve of Diwali two years ago, P Radhakrishnan was busy in the kitchen making his 83-year-old mother’s favourite dish – the South Indian dosa – when she managed to slip out of the house. If it were not for his wife, who, while returning home, noticed Seethalakshmi, stranded on a street nearby, totally disoriented, things could have gone terribly wrong.

Memory impairment is often a precursor of this crippling illness and the resulting actions or behaviour can be problematic.

Gomathi Radhakrishnan recalled that momentary lapses in memory had become reasonably common with her mother-in-law, in the last couple of years preceding this incident. The family did not read too much into it, as they presumed such occurrences were part of old age.

Finally, an episode of outrageous behaviour, which was out of character for her, proved to be the last straw and drove the family to seek medical intervention. “We had to go out of town so we decided to leave [my mother] under my brother’s care,” P Radhakrishnan said.

Whenever there was a family function and I had to wear a nine-yard saree, she’ll come running to me and will herself drape that nine-yard on me.

Gomathi Radhakrishnan

Gomathi Radhakrishnan added: “She is someone who has never resorted to any sort of aggression ever but out of nowhere unleashed havoc on his family that night. We brought her home from [my brother-in-law’s house]. She behaved the same way the following two days, she’d say, ‘My father-in-law is sitting in the verandah and is asking for a cup of coffee. Open the door, I have to go.’ She will then go on hitting the front door and banging her head on it.“

Dharam Priya Mahandass’s Story

“He was obsessing about certain things and being very manic, repeating himself throughout the day especially when it came to matters of work,” Mahan said of his father, Dharam Priya Mahandass.

Varun Mahan, 33, a British citizen of Indian origin, was on the cusp of adulthood when he first got a glimpse of his father’s erratic behaviour. But the gravity of the situation hit him when he was “well into his twenties”.

“Sometimes if you flipped his switch, he would gather his things and literally run out of the house,” Mahan said. “You’d have to follow him and say, ‘Calm down. What’s the matter?’” To make matters worse, whenever Mahan proposed that his father needed to consult a psychiatrist, it would be met with the standard accusation: “You want to put me away.” When Mahandass was finally brought in for a psychiatric evaluation after much coaxing, he was handed a “clean bill of health” by the examining doctor.

The thing I miss the most about him is leaning on him for advice or mentorship. It’s very difficult when you have a teacher who you rely on so much and you don’t have that person to turn to anymore.

Varun Mahan

He is currently undergoing treatment at the Schizophrenia Research Foundation in Chennai. While addressing a monthly dementia support group meeting, Dr Vaitheswaran, who specialises in old age psychiatry, affirmed that medical assessment and intervention are paramount in helping a PWD. He added that supplementing medication with psychological intervention – behavioural management – is key to the person’s well-being. Finally, he stressed that a caregiver’s well-being and competence play a crucial role in improving their dementia-afflicted loved one’s quality of life.

V Ramachandran’s Story

Maya Ramachandran lost her father, V Ramachandran, in 2010 after his grievous descent into dementia. It was spurred by a road accident in the summer of 1994. Her father, then 57, had just left the house on his two-wheeler to pay his sister a visit, with Maya, the youngest of his four children, on the pillion. Maya was just 23 then. As a bike collided into them from the side, they were thrown off their two-wheeler.

Maya heard her father’s skull split on impact. Blood began oozing from one of his ears as he lay unconscious in the middle of the road. Simultaneously, he started to froth and have seizures.

Maya managed to collect herself and took care of her father’s epileptic fits. He was admitted to hospital. Medical reports showed that Ramachandran had suffered a hairline fracture of the skull – one of his temporal lobes had been affected in the process. After recuperating in the hospital for a month he came back home but a different person.

For us to even recognise him was difficult because he was very irritable, highly disoriented, confused about our names, who we were and a lot of things like that. From a point where he didn’t know how to identify alphabets, he took a small-time job as an admin manager near our house.

Maya Ramachandran

These good times were short-lived: her father soon developed tuberculosis (of the chest and spine), following which his mobility was greatly hampered. Regular physiotherapy sessions allowed him to walk again, albeit with some form of support. The passing away of his wife (due to cancer), who was also his primary caregiver, in 2009, turned to be the final nail in the coffin. “That is when he actually started withdrawing,” Maya said. “For sometime he managed but after that I think he started feeling very lonely because [my husband and I] used to go to work leaving him under the supervision of a paid caregiver.” His disorientation spiked towards the end, so did a host of other health problems.

Ramachandran breathed his last on August 8, 2010, in a hospital bed with Maya singing a lullaby by his side.

Savitri Vishwanathan’s Story

Savitri was diagnosed with dementia in 2012. The illness had crippled her to the point where she needed constant prompting and considerable assistance with basic activities, such as eating and walking. Her son, Komal Vishwanathan Balachander, was deeply harrowed by his mother’s near-comatose state. “For me to come and see her in this condition is quite difficult, I’d rather not do it,” he said.

Although Savitri lost her husband in 2001, her daughter-in-law said she did not lose heart, and managed to accomplish a great deal even after his death, like expanding her bungalow’s first floor into an independent unit and making several solo trips abroad. She recalled herself comparing Savitri to her mother, and she didn’t like the feeling too much. Sometimes, we don’t know any better. A mother, regardless of who the child is, will always be a – mother. Care is more than just a physical presence, it the system one puts in place for caregiving within the humane bounds, and a dignified treatment.

She really took the bull by the horns. My mother-in-law’s well-being is partly due to my husband’sdecision of not sending her to a nursing home.”

Daughter-in-law

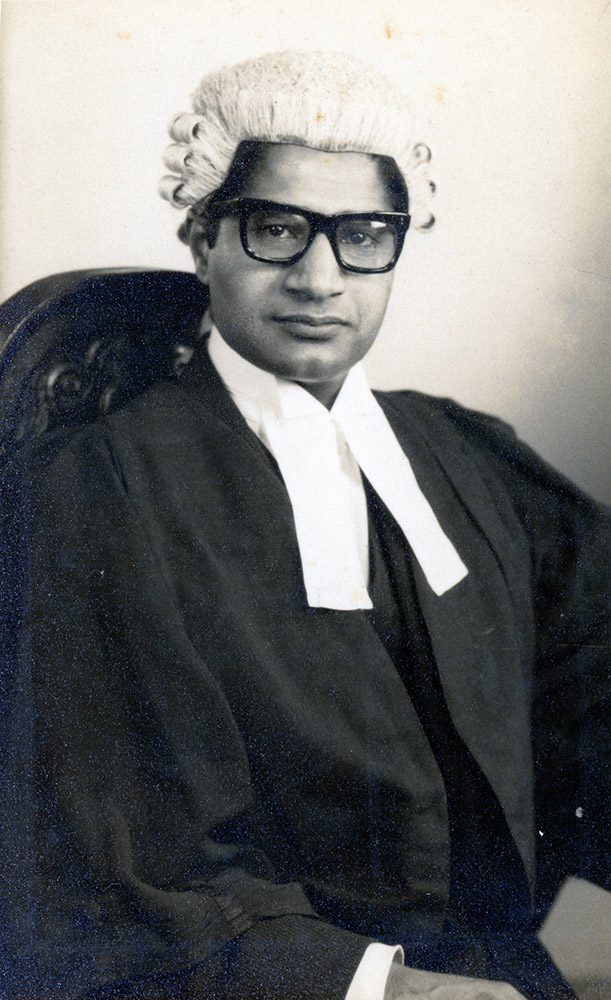

PS Krishnan’s Story

In a common Indian environment, a person with disabilities (PWD) typically has at least two caregivers, often family members, to assist with their daily needs. But Chitra Sundar and Sita Krishnan, take care of their other halves all on their own. Krishnan is married to PS. Krishnan, and Chitra is married to E Meenakshisundaram’s

“[My husband] says, ‘My wife is dead and gone.’ So, I ask him, ‘Who am I?’ ‘I don’t know who you are but I thank you for taking care of me,’” Krishnan said.

Her husband, PS Krishnan, 89, was a general practitioner who had a clinic of his own not too long ago. As he started displaying signs of dementia, the rest of the family decided it was in everyone’s best interest that he discontinue his practise.

After his diagnosis in 2013, he remains house-bound, owing to his deteriorating mental health and laxity in his legs. He does make time, however, to flex his vocal cords with a few devotional songs every other evening, largely upon his wife’s insistence.

“It’s not easy for a caregiver. Sometimes, I just give up. Those are the times I really feel bad for what I have done. The other thing is that this disease in no way is going to become better so [the doctors] have asked me to be prepared for the worst so that’s what I’m doing – it takes a lot of determination and courage. I did have all that but now I think I’m losing it.”

Sita Krishnan

He is not always at his best behaviour. After an untoward incident involving him and the LPG delivery person two years ago, his wife realised she had to stay on her toes whenever they had company.

When they are by themselves, she has to deal with his unfounded, often abusive, rants about not having cash, clothes, being a “madcap” and not being able to practice.

She and her husband moved in with their second son, Arun Krishnan, and his family in Bengaluru. “I felt a change of environment would do him a world of good,” she said. “Besides, having my son around to share some of my responsibilities would in turn help me lead a balanced life.”

“There is a God: He has his own ways,” Krishnan said. “I’m accepting that.”

E Meenakshisundaram’s Story

E Meenakshisundaram, 68, had retired as a senior-level executive in 2008 after an illustrious career in a massive public sector enterprise. He had always had a bit of a temper, which became more intense and recurrent in his golden years. This prompted his wife Chitra Sundar to consult a neurologist, who told her that he would never again be the man she once knew, loved and admired.

Right from his morning routine, I have to be alert and patient. Sometimes, he is constipated for days and cannot express his discomfort or pain as he has lost his ability to articulate.

Chitra Sundar

This was back in 2011. Over the past two years, Meenakshisundaram has metamorphosed into a toddler of sorts, in constant need of attention. Chitra Sundar, meanwhile, has come to terms with her partner’s excruciating decline. The added responsibilities on Chitra Sundar’s shoulders have taken an immense toll on her mental and physical well-being.

I know things are going to get worse in the days to come. I pray and hope that I find the strength and courage to take care of him in the upcoming years. My only wish is that I outlive my husband so that our children don’t suffer.

Chitra Sundar

The children have been Chitra Sundar backbone in times of need. Settled elsewhere, they have often tried their best to persuade their mother to move in with them along with their father. This steadfast, resilient woman stayed put. She reasoning is simple: she neither want to burden the children nor subject her husbands to unnecessary stress.

Dementia around the world

Unlike the West, institutionalised care is frowned upon in India. Family members are usually the only caregivers in charge of someone in the family struggling with a disorder such as dementia – the major reason being the strong family and social system prevailing in the subcontinent. Joint families are still somewhat common in urban areas but are certainly the norm in towns and villages. If an elder in the family falls sick, or is diagnosed with a chronic condition, the entire household rallies to help get them back on their feet. But the changing social context here, in particular, the brain drain and mushrooming of nuclear families in urban centres, influenced by a number of factors such as westernisation, is placing considerable strain on dementia caregivers looking after their loved ones.

According to the World Health Organisation, there are around 55 million people in the world living with dementia. India is home to 16% of that population. Elderly folk, of 65 and above, are most susceptible to fall prey to this affliction. To exacerbate the already grim situation, there is a dearth of trained specialists in India. According to a study by the Indian Psychiatric Society, there are just 9000 psychiatrists in India. This translates to 0.75 psychiatrists for every 100,000 Indians (compared to six psychiatrists per 100,000 people in high-income countries). In fact, there is a shortage of 27,000 doctors in the country.

Challenging behaviours like these are fairly common among Persons With Dementia. Deficits in a PWD’s cognitive abilities give rise to changes in behaviour and can lower their inhibition. Around 90% of PWD generally manifest some kind of challenging behaviour. Family members are often left in a fix when their loved one’s abnormal behaviour gets out of hand.

As if this weren’t enough, lack of awareness and societal stigma towards mental health and mental illness also play a significant part in families often refraining from getting professional help. Plus, secondary options like hospice, palliative or home health care leave much to be desired.

The writer would like to thank the featured families and the Schizophrenia Research Foundation for their generous support.