Table of Contents

Disclaimer: This blog contains sensitive pictures and facts.

In the serene coastal village of Taiji, Japan, a dark tradition plays out every year from September 1st to March 1st. This event, known as the Taiji dolphin hunt, has drawn international condemnation for its brutality and questionable motives. Featured in the 2010 Academy Award-winning documentary The Cove, this six-month-long practice exposes a harrowing reality: the large-scale capture and slaughter of dolphins, all under the guise of cultural heritage.

The Mechanics of the Hunt: Profit Over Tradition

Each year, the Japanese government issues quotas allowing the slaughter or capture of over 2,000 dolphins and other small cetaceans, making this hunt one of the largest of its kind in the world. The dolphins are driven into a cove by a fleet of motorized boats creating a “wall of sound” that disorients these sonar-reliant creatures. Trapped and terrified, the dolphins are either selected for live trade to aquariums and marine parks or slaughtered for their meat.

The economics of this trade reveal a dark truth: while a dolphin killed for meat might bring in about $600, a live dolphin, especially a bottlenose, can fetch upwards of $100,000 in the global aquarium market. This disparity in value has turned the hunt into a profit-driven industry rather than one based on traditional subsistence. The practice of capturing dolphins for display rather than for community sustenance only began in the late 1960s, contradicting claims that the hunt is purely a cultural tradition.

Declining Numbers: A Hollow Victory?

Recent years have seen a significant decline in the number of dolphins captured or slaughtered in Taiji. During the 2023/2024 season, only 415 dolphins were taken, a historically low number compared to the quota of 1,824 set by the Japan Fisheries Agency. Activists see this as a positive trend, yet it raises questions about sustainability and the future of dolphin populations near Taiji. Overexploitation, environmental changes, and possibly even the effects of climate change could be pushing dolphin populations away from the Taiji coast, leaving the hunters with fewer dolphins to capture or kill.

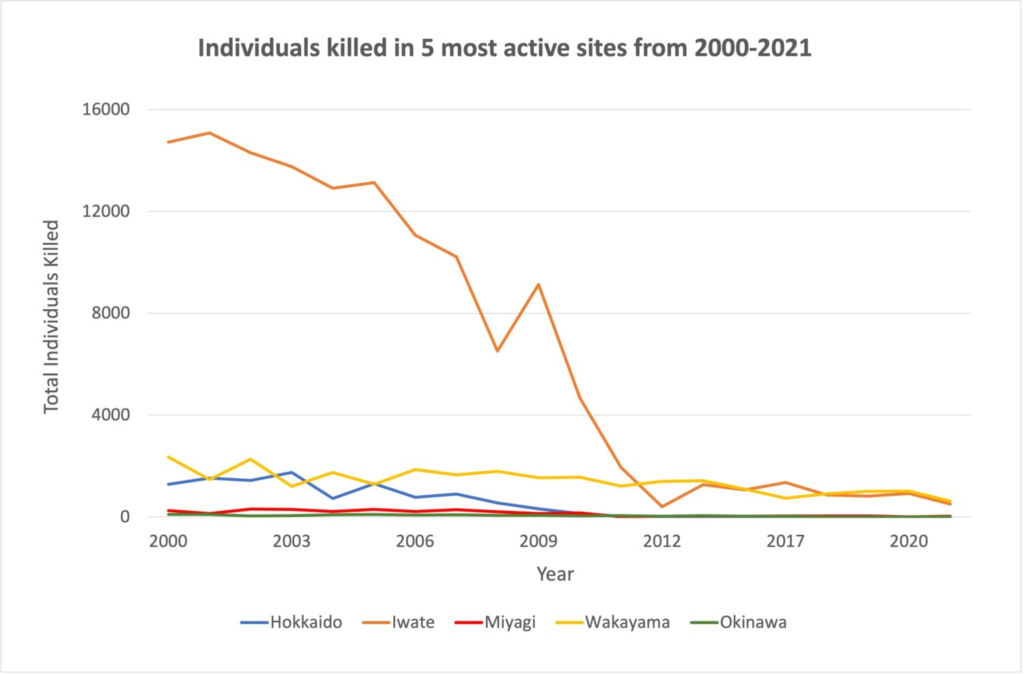

Japan’s dolphin hunts experienced a dramatic shift between 2000 and 2021. Data from the Japan Fisheries Agency reveals a steady decline in dolphin killings and captures for captivity, particularly in hotspots like Wakayama and Hokkaido. Taiji, infamous for its dolphin drives, saw a marked decrease as represented by the yellow line on the chart.

The once-thriving dolphin hunt in Iwate Prefecture, symbolized by the orange line, was decimated by the 2011 Fukushima disaster, which crippled the region’s fishing industry. This event serves as a stark reminder of the industry’s vulnerability and the environmental challenges it faces.

Health and Environmental Concerns

The consumption of dolphin meat, known locally as “taiji gyorui,” has long been part of the diet in certain regions of Japan. However, it comes with significant health risks. The meat contains dangerously high levels of mercury and other toxins like methylmercury and PCBs, which accumulate in the fatty tissues of these apex predators. Independent tests have shown mercury levels in dolphin meat that far exceed the government advisory limit, posing severe risks to human health, especially for pregnant women and children.

The impact on the environment is equally concerning. Dolphins play a crucial role as apex predators in maintaining the balance of marine ecosystems. Their removal in large numbers threatens to disrupt this balance, leading to cascading effects on marine biodiversity and the health of ocean ecosystems. Moreover, the live capture industry has broader implications, as dolphins are transported globally to marine parks, where they often suffer from stress, cramped conditions, and shorter lifespans. Not widely discussed are the health risks to the hunters themselves, who are exposed to potential pathogens when handling and butchering dolphins. This aspect adds a layer of complexity to the debate over the continuation of these hunts.

Japanese Government and Industry Response

Despite the international condemnation, the Japanese government continues to defend the hunts, citing legal grounds under its Fisheries Agency regulations. The government argues that dolphins are not endangered and that the hunts are sustainable. However, this position is not without its critics within Japan. Japanese citizens and activists call for stricter regulations, greater transparency, and a reconsideration of the practice in light of modern conservation ethics.

The International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling, imposed in 1986, does not apply to dolphins, classified as “small cetaceans.” This legal loophole has allowed Japan to continue these hunts despite growing global opposition.

Is there a future for Dolphin Hunting in Taiji

As the world becomes more aware of the ethical and environmental implications of dolphin hunting, the future of this practice in Taiji remains uncertain. The declining demand for dolphin meat, driven by health concerns and changing consumer preferences, along with the potential collapse of the live dolphin trade, suggests that this brutal tradition may not be sustainable for much longer. The COVID-19 pandemic has further impacted the industry, with exports to China blocked and many captured dolphins left waiting in sea pens for buyers who may never come.

Activists and organizations like the International Marine Mammal Project (IMMP) of Earth Island Institute continue to work towards reducing the number of dolphins killed for meat by publicizing the dangers of mercury contamination. Their efforts are slowly bearing fruit, but the battle is far from over.

As we’ve explored, this annual event is not just a local tradition but a global concern, with significant implications for animal welfare, public health, and marine ecosystems.

Your voice matters in this conversation. We invite you to share your thoughts, perspectives, and experiences in the comments below. Engaging in dialogue is one way we can all contribute to the growing awareness and pressure needed to bring about meaningful change.

If this topic resonates with you and you’re passionate about writing on such critical issues, we encourage you to join our community of writers. Whether you have a story to tell or an analysis to share, we want to hear from you. Send your pitch to [email protected]